|

Secret Identities:Unmasking the Creators of Watchmen

The identity of comic book writers and artists are rarely evident when looking at most works in the superhero genre. This is perhaps due to the fact that superhero characters are usually created with stereotyped attributes (i.e. Superman's protection of humanity, Batman's quest for justice) that they must always adhere towards. Also, the major comic book publishers, more often than not, like to keep the stereotyped depictions of their characters consistent. In the rare instance that an artist or writer has creative control over a new or established superhero, they still have to maintain an industry standard format. If the creator(s) were to impose personal belief or bias, the superhero persona might be lost and the book might not sell. When DC Comics released the twelve issue series, Watchmen, in 1986, it introduced a new form of identity perception in comic books. I'm not referring to the identity of the creators, but rather that of the reader to the comic itself. With Watchmen, writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons were able to change the standard impact of superhero comics, not by imposing their own identities, but rather by targeting the series to be read by a mature audience. By turning the focus on audience reaction, the identity of the reader is more important to Watchmen, rather than that of the creators.

I don't want to imply that there are no aspects of the creators' identities in Watchmen, but those that exist are few and far between. To better understand this, let us briefly look at the histories of the artist and writer, and how Watchmen fits into their body of work. In the 1973, Dave Gibbons started drawing for British comic magazines such as 2000 A.D., working on strips Rogue Trooper, and Dan Dare. Alan Moore began scripting comics in 1980, also contributing to 2000 A.D. for the popular Doctor Who strip. Moore also worked on the British superhero book Marvelman , and the thriller V for Vendetta, which earned him a British Eagle award for Best Comics Writer in 1983. DC Comics tapped several British comics writers and artists in 1982; Gibbons was selected to draw Green Lantern, while Moore started scripting Swamp Thing, which garnered him more awards in both England and the United States. Watchmen was published in 1986, first in individual issues, and later in a collected graphic novel format. Moore has gone on put his realist spin on other superhero projects, and other mature themed projects like From Hell, a graphic novel about Jack the Ripper. Gibbons has also worked on other superhero titles, as well as a comic adaptation of the Bible and several other mature themed projects.

Does the fact that both creators are British affect their influence on Watchmen? No. Does their past work have an influence? A little. Watchmen takes place in America, and deals with the mythos of American superheroes. Because it was written during the mid-Eighties, there is a portion of the plot that deals with Nuclear scare from possible war with Russia. England is only brought up once, vaguely, in a government nuclear scenario where it would be destroyed along with most of Europe. Again, the driving force here is the superhero, and the fact that the superhero genre was predominantly American makes the United States the default setting for Watchmen. As far as previous work, the fact that they both worked in the mainstream superhero genre gave them something to react to. They had to know what they were trying to mature, and by having stints on superhero books, they had a pretty good idea.

If there is a personal identity that comes through from either creator, it would be that of Moore's. It can be derived from past interviews and other works that Alan Moore does not like superheroes. He only uses them because they dominate the medium of comics. In a critique on Watchmen, it is pointed out how Moore creates this 400-page accusation on the superhero genre, presenting the heroes as Communists, abusers of women, psychotics, egocentric, and suicidal. The question is proposed, "if Moore doesn't like or respect his characters, how can the reader be expected to?" As the writer, Moore asserts more control over aspects such as characterization, cultural and political references, and the creation of the world itself. There is a "multimedia" approach to the narrative that gives Moore several ways to get his point across. There is the use of Dr. Manhattan's narration, Rorschach's journal entries, selections from Hollis Mason's autobiography, psychologist reports, newspaper clippings, and even a pirate comic book. There is also the constant use of flashbacks, where the same event is explored from various viewpoints.

This is not to say that Gibbons has no control in creating the world in portrayed in Watchmen, but the sheer amount of textual information given in the series makes Moore's voice almost overpowering. Gibbons understands that these aspects are important, so instead of using a flashy attention-grabbing style of art, his pictures are quasi-realistic renderings of the characters and the world they live in. This art style allows the reader to concentrate on the story, which is designed to be what sets Watchmen apart from other superhero comics.

This brings us to the reader identity and how Watchmen is perceived by its intended audience. Moore and Gibbons understood that the superhero genre was as tired as the motifs used to create characters. Competing publishers had created carbon copies of Superman, Batman, the Flash, Spider-Man, and X-men. Storylines had been recycled since the Forties, and the original ideas for plotlines had become scarce. This dismal assortment of material was causing the audience to become more and more categorized as adolescent boys with a short attention span for violence and scantily clad women.

Instead of catering to these comic book fan-boys, Moore and Gibbons set out to create their own audience: people that they assumed would want to be challenged and intrigued by their reading material, and others who had been comic readers in the past. Moore and Gibbons were willing to spend two years on creating the project, while DC Comics, having worked with both creators and looking for an underground hit, were willing to support it. It was first published in comic book format, in twelve separate issues. But when it was later published as a graphic novel, newsstands and bookstores made it available to a wider audience. Because of the "novel" format, it became a little more socially acceptable for hesitant buyers to check it out. Word of mouth and buzz among fans have kept the series a favorite in the industry for almost fourteen years now.

Most readers of the series when it came out would be more affected by the issues in the comic dealing with nuclear war, the Russians invading Afghanistan, and Nixon as president for five consecutive terms. Readers of Watchmen today might not be interested not so much by the politics, but by the overall plot, and also the impact it has had on the industry. Friends, comic collectors, bookstore employees, or even a University setting, where it has been used as a textbook in modern fiction classes, have most likely referred today's readers to Watchmen.

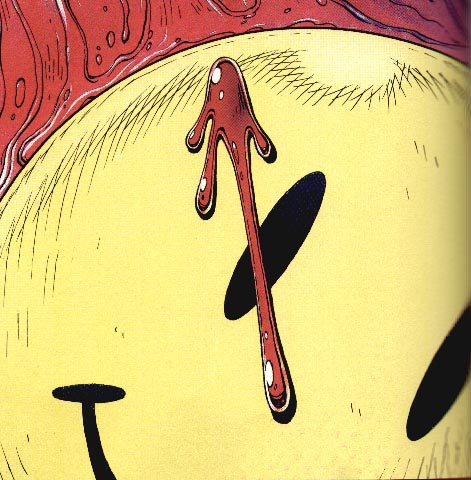

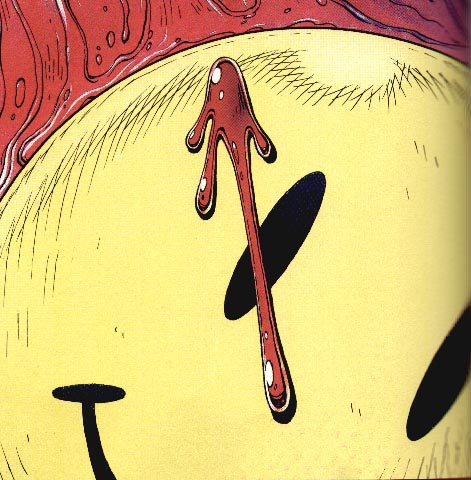

The effects of Watchmen on readers will also hold true throughout time, and none of them have anything to do with the identity of the creators. Although there is mention of 1980's political happenings, most of the series concentrates on the characters, their relationship to each other, and as superheroes. Readers are given a new perspective on superheroes. They might admire this, or be disgusted by it, but the fact that these superhero characters affect them is a powerful statement. Like a complex book, readers are likely to re-read Watchmen multiple times to pick up on new visual symbolisms and recurring elements. Because the work is challenging and intellectual, the reader is lead to evaluate their views not only on issues raised in the comic, but their views on the comic itself. The only association a reader might have for the creators is to remember their names to either collect or avoid other works by them.

In interviews, Moore said that he intended Watchmen to be the definitive superhero series that would bring an end to the superhero genre altogether. Many fans might agree that this goal was reached, but I find it a bit presumptuous on Moore's part that he wanted superhero comics to end. I also find it a bit ironic that Moore has taken on writing assignments on superhero titles since Watchmen, and even created some of his own. In any case, I feel that Moore and Gibbons created a work that, even if disliked by some readers, was viewed by more readers than just the stereotypical teenage boy fan base. It brought comic book awareness to many, but more importantly, it demonstrated what comic books can do and how much they can affect the reader. I think that what Moore and Gibbons really wanted was what most comic creators want: respect for an often laughed at genre, and medium.

Watchmen©1987 DC comics all views expressed in this paper are those of Chris Daily and do not reflect those of DC comics, Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, the Pope, martians, Julia Child, the Dutch, small dogs, or your mom. Use of this paper is under the exclusive permission of Chris Daily, so ask, okee? e-mail: toonsniper @ hotmail.com

|